Uglier than Da’esh: After ISIS is Defeated in Mosul

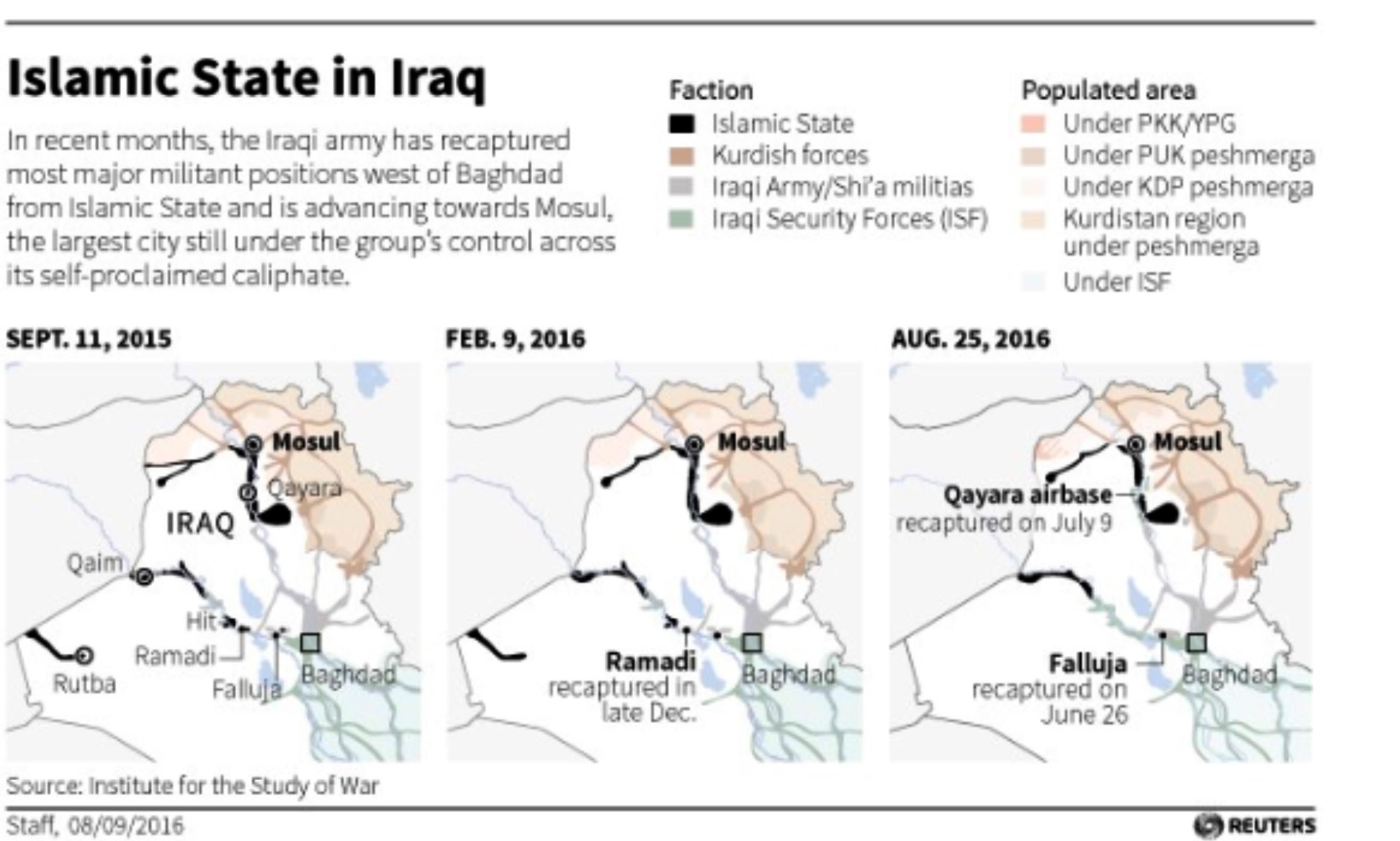

A long-awaited campaign to reclaim Iraq’s second largest city of Mosul from ISIS is now just weeks away. Yet those that think the liberation of the city will set the course for stability and reconciliation in the country should think again. For most Iraqis, ISIS is a two-year problem inside of decades of grievance and social conflict that birthed the extremist group in the first place. In the contest of power that is northwestern Iraq, too many Iraqis feel that what will follow moves to reclaim Mosul will be “uglier than Da’esh”, to use the local term for the Islamic State. This is why.

Mosul fell to ISIS in June 2014, but many residents will tell you that the city had “fallen” long before. Under Saddam Hussein, the historical diversity of the city suffered as Hussein promoted a syncretic blend of Ba’athist-Salifism to shore up support among his Sunni Arab base for campaigns against Iran in the 1980s and the restive Kurds in northern Iraq throughout the 1990s.

When Hussein fell in 2003, Sunni dominance of national politics ended as Shi’a Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki sought to limit the legislative and military influence of Sunni and Kurdish groups in the country. In Mosul, this marginalization inspired Ba’athist and Salafist Sunni Arabs to form armed groups and criminal enterprises that too often collaborated with elements of the Iraqi army and local officials to enrich themselves through extortion, corruption, and the confiscation of property owned by minority Yezidi, Shaback, Kakai, Turkmen, Christian, and Shi’a residents. The entrepreneurial Islamic State leveraged Sunni fears and continued this trend, consolidating power among competing groups and promising its own brand of lethal justice and exclusion in place of autonomous armed groups and corrupt authorities, not unlike the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

On the eve of an expected victory over ISIS, real and imagined signs of political and cultural marginalization of Sunni Iraqis continues to drive instability in the country. The recent firing of Defense Minister Khaled al-Obeidi, a Sunni from Mosul, and the participation of Shi’a Hashd ash-Shaabi fighters in the planning and execution of moves on Mosul are reinforcing Shi’a – Sunni tensions. There are emergent rivalries within the Sunni community with figures like Nineveh governor Nofal Hammadi and former Nineveh governor Atheel al-Nujaifi positioning to fill the political void that a defeat of Da’esh will leave behind. And finally, Baghdad and Sunni leaders both distrust the intentions of Kurdish forces advancing into new territory in the north near Mosul. A sense of persecution, mistrust, and political opportunism will characterize “the day after ISIS” for well-armed and disparate adversaries in the country.

Add to this the potential for retributory violence by Yezidis, Turkmen, Christians, Shi’a and others that lost family members, homes, and livelihoods to ISIS and the future is even more forbidding. The documented human rights violations that many displaced Sunni Iraqis now endure at the hands of Yezidi and Shi’a militants hints at the very real possibility of widespread discrimination against additional displaced Sunni residents flowing from Mosul, as well as those trying to return to their homes. This will sharpen the sense of victimization that justifies Sunni separatism and militancy, in turn fueling the spiraling counter-measures that are the response.

How may we best navigate a post-Islamic State era amid these forces that would tear at integrity of the state and undermine the social and economic potential of so many of its residents? Lessons from earlier engagement in Iraq and from intense identity-based conflicts in the Balkans, the Caucasus, Myanmar, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and elsewhere suggest the following:

Help the displaced return home.

In a world filled with record numbers of forcibly displaced persons (65 million and counting), nothing nurtures grievance like the social isolation and impoverishment that accompany exile. Since April 2014, 3.3 million Iraqis have been forced from their homes. An estimated 70% of these individuals are Sunni Iraqis displaced by conflict in the west and north of the country. Another 800,000 persons can be expected to rush from Mosul and surrounding areas once the campaign begins – a number that will overwhelm humanitarian aid providers that describe the prospect as a “nightmare headed our way”. Fragility shadows such displacements and stability and economic growth will remain elusive in Mosul unless these vulnerable, disenfranchised citizens are assisted to return to their homes or integrate in place.

Sustainable return will require restoration of basic services, housing, and livelihoods.

The slow pace of returns to Fallujah, liberated from ISIS in June 2016, is partly attributable to a continuing lack access to clean water, electricity, and health services. Integration or returns to neighborhoods and villages is also not viable without reconstruction of housing, transparent and rapid adjudication measures to solve property disputes, and economic programs grounded in the recovery process that benefit residents, returnees, and those that choose to remain in exile. In Mosul alone, it is expected that over half the housing stock of the city may be moderately to significantly damaged by the time a liberation campaign ends. Putting people to work in the rehabilitation of services and housing in their own home areas is an approach that succeeded in reviving local economies in Bosnia, Sri Lanka, East Timor, and Lebanon, for example.

Stability will require a layered security approach.

Security within the current environment of suspicion and mistrust may require a layered approach to policing, with local police managing discrete geographic areas and domestic affairs while federal police and national military units like the 9th and 16th divisions safeguard freedom of movement, employ reasonable vetting processes, and ensure protections are in place for all residents living within or wishing to return to the city. Variants of this approach helped stabilize post-war cities like Brcko and federated areas of Bosnia, as well as areas of Kenya affected by election-related ethnic violence in 2007-2008.

“Building back better” will require good governance.

Nothing will signal “more of the same” and fuel resurgent factionalism than a revival of the kleptocracy that was local governance in Mosul before (and during) occupation of the city by ISIS. A far better approach is to put to use bottom-up community-driven planning and prioritization processes as used in Afghanistan, Myanmar, Lebanon, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and the West Bank and Gaza. Couple this with “one-stop-shop” administrative centers like those in conflict affected areas of Ukraine, Colombia, and Georgia where residents can efficiently pay fees, register births, obtain required legal stamps, file complaints, and replace lost documentation. These are tested methods that, when done well, invite legitimacy, patience, and faith in fragile recovery processes.

Former and current militants and trainees not responsible for crimes will require reintegration.

Perhaps most important will be the identification and rehabilitation of minors aged 9-12 trained as “Ashbal al-Khilafa” or “Cubs of the Caliphate” to carry out “jihadist operations”. But many more individuals have been involved in organized violence prior to, and during ISIS’s control of the city. For those not implicated in criminal activity, disarming and reintegrating these individuals into civilian life will be difficult – but programs in Sierra Leone, Lebanon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Colombia, and Pakistan show successful results are possible, if not always sustainable.

Finally, reconciliation is a long shot – but even peaceful coexistence will be an improvement among the city’s diverse ethnic groups.

To begin, a “working consensus” among the city’s adversarial factions will be required to address recovery challenges and allow good governance to take root. Sustaining an ethic of “live and let live” will be difficult enough but shared governance structures and collaborative efforts among oppositional groups to address common service delivery deficits have proven to be among the best ways to maintain focus on mutual interests. A focus on developing a “working consensus” will also require that civic infrastructure continues to mix populations in market spaces, parks, and recreation facilities. For those found complicit in criminal activity and human rights abuses, public and balanced transitional justice mechanisms must hold perpetrators accountable while revealing the consequences of their actions. Moving toward confidence and trust will require these criminal prosecutions, restorative justice, reparations in select cases, truth commission work, and institutional reforms to broaden public participation in local and regional governance. These were among the methods employed to move from the intractable to the possible in Kosovo, South Africa, Guatemala, Cambodia, Bosnia, Serbia, East Timor, Liberia, Rwanda, Lebanon, and Macedonia.

These are not the only recovery responses that are important but they will go a long way toward promoting stability in a city that has endured years of divisive violence – and will likely suffer even more in the campaign against ISIS. Planning for these kinds of post-ISIS recovery activities should have begun two years ago. Far too much attention and technical expertise has been taken up in the humanitarian response to forced displacement and military planning for Mosul’s liberation. Far too little focus has been on what a recovery and development approach to normalizing the city and region will require. It is not too late, but it will be much harder to get it right at this point. What will truly be devastating is to simply declare “mission accomplished” once the Islamic State is removed from Mosul. Without concerted recovery and development planning and rapid response after the military campaign ends, what will ensue post-ISIS may not only be “uglier than Da’esh” but also much more difficult to contain and reverse.

Ray Salvatore Jennings is Founder and Principal of the Cultural Navigation Group and a Senior Consultant with the World Bank and USAID.